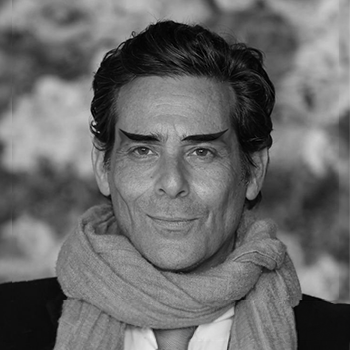

The conference table carried a scatter of mugs, some mismatched; the ship’s neat aesthetic briefly vandalised by ordinary life. Ayres stood at the far end, sleeves rolled to the cuff, uniform slightly unbuttoned. He had learned early how a different appearance could put people at ease, bridge the gap between cultures and expectations.

Parr was seated to his right, a PADD ready, as much a prop as for taking notes. Vennock, the ship’s doctor, was the only other member of the crew in the meeting, looking taciturn but not wholly unwelcoming.

Opposite them, the visitors from the Kelzora arranged themselves with the self-consciousness of people who had never entered a room like this. They were not a delegation, not really; more a collection that had congealed into responsibility by the sheer act of survival. The freighter’s master, a broad-shouldered woman called Donis, sat squarely, the sort of posture that dares anyone to argue with her. Beside her, a young man with a careful face and hands that kept rehearsing apologies; a wiry older man whose voice had the low timbre of someone who had spoken too much when young and now enjoyed the accidental gravitas; and a child, perhaps eleven, whose official permission to be present had been secured by the fact she refused to unclasp her hand from Donis’s sleeve. She watched everything. Her name, someone had told Parr, was Lin.

“Thank you for coming,” Ayres said. “I know you’ve had a long day. You’re safe here. And I’m glad to see you’ve made use of the replicators. We can ensure you have what supplies you need when we finish up.”

Donis nodded. Not particularly in gratitude but in recognition.

“We’re Starfleet,” Ayres said, because that, too, was hospitality: say who you are. “We’re the exploratory arm of the United Federation of Planets. That’s a mouthful.” Ayres looked at Parr, hoping for some help. She deliberately remained looking at her PADD. “The short version is that we’re from a large collection of planets that see our purpose as, mainly, to help. We do that partly because of our relative abundance,” he gestured at the replicator again. “And more importantly because we believe that when societies, civilisations, and species come together, we all benefit.”

Donis looked at him with a weighing expression. “You’ve got a big warship,” she said. “What does your help and protection cost?’”

“I’ll take it,” Parr murmured, a softness that got a flicker of a smile from Ayres. “The cost is your time. Some time to listen to us, to talk with us, to share ideas and information about where you come from, what your worlds are like.” She smiled broadly. “You might come to like us.”

The anxious young man cleared his throat. “We didn’t know that people like you were real,” he said. “No offence.”

“None taken,” Ayres said. “The change in this part of the galaxy’s physics – we call it the Shackleton Expanse – meant that the difficulty of exploration was too great. We’re making up for lost time. Without trying to alarm anyone.” He rested his hand on the table’s edge, opened his palm. A small, unthreatening gesture. “We would like to understand who hurt you. You called them pilgrims.”

Donis’s jaw worked once. “Not we,” she said. “Some do. Some call them that because that’s what they call themselves. We said raiders. Criminals. Fanatics. They don’t deserve the honour of being called pilgrims.”

“What do they call you?” Aloran asked, neutral.

Donis’s mouth twitched. “Depends whether they’re preaching or just murdering people. When they preach, they call us brothers and sisters.”

A small sound from Lin. Not a word, a pressure of air, the spark before speech. Donis glanced sideways. “Say it,” she said without softness, which Parr understood as a particular kind of love.

“They sing,” Lin said.

Ayres, Parr and Vennock did not look at one another; they had learned that trick, hide the questions and let others fill in the details around your silence. Vennock only tilted her head a fraction in a gesture that meant ‘go on’ without putting the weight of expectation on a child’s chest.

“In the walls,” Lin said. “Before we knew. We were at supper and the wall hummed. Grand said it was a fan; he tapped it with his ring to make it stop showing off. But it kept trying to be a song.” Her small hand made a circling motion, seeking a word it did not yet own. “Like someone talking through a door.”

“What happened after the humming?” Parr asked, her tone low and kind.

“Lights went strange,” The young man answered, grateful to relieve the girl. “Not failing. Like they were thinking about failing. Then the first knock. Then four knocks, then the heat went odd and all the computers started behaving like they were on someone else’s ship. And the singing got louder”

The older man, who had said nothing, folded his hands. “Aye,” he said. “On the lanes. On the old road from Veil’s Edge, you hear talk. Folk like to label fear. The Pilgrims go ship to ship, they say, making gifts you don’t want. They’re tidy with it, mind. They know how to fight, don’t seem to care if they die. Helps to fight if you don’t care if you die.”

“What do they want?” Ayres asked.

“Want’s the wrong word,” Donis said. “They believe. And they think we ought to.”

“What do they believe?” Vennock’s voice was careful.

“That flesh is a cage and mercy is an opening,” the young man said dully. “Entropy is the cradle of light. The singing doesn’t make sense.”

Parr allowed herself one brief, audible breath out through her nose, which in her private book of liturgies was the sound for ‘that’s an understatement’. “Do you know how many there are?” she asked.

“No. Lots? You saw their big ship. Then they seem to amass the smaller ones quicker than any of us can defend against them,” Donis said. “They seem to appear wherever they want in the lanes. But unpredictable. It’s not like there’s one route or specific sectors to avoid.” She jerked her chin towards the window. “We’re not stupid. If we could avoid a fight like that, we would.”

“Anyone would.” Ayres said sympathetically. “And their leader?”

Donis and the young man exchanged a glance that had the shape of an old argument. “A man,” Donis said. “Spoke soft. Mask that looks like a skull. They all wear those damn masks. But his is different, like it’s the mask from which all the others are mimicking.”

“Did he give a name?” Parr asked.

“Prophet,” Lin said, with the certainty children save for the parts of horror that adults try to speak around. “He said he was the prophet and that we could be pilgrims if we weren’t frightened.”

“What happens to people when the pilgrims board their ship?” Vennock asked. “Do they take particular interest in children, elders, anyone sick?”

Donis’s eyes narrowed. “They’re particular. Like they’ve got a ledger. But I couldn’t figure out who and what they want. None of the shipmasters can. They look at you and call you sister, brother, and ask you if you want mercy with a voice like a lullaby. And if you say no, they call you brave and kill you.” She tapped a finger on the table. It sounded like a gavel. “And if you say yes, they call you brave and kill you.”

“They can’t kill everyone?” Vennock asked.

“They don’t,” the older man said softly. “If you sing.”

“It’s not really singing,” the young man said. “It sounds like prayer. But my father would have called it propaganda because he didn’t have patience for mystery. It sits somewhere in between. And sometimes it sounds like it’s coming from the ship, or that the people who start singing it are singing with the ship.” He looked down, embarrassed at his explanation. “Sorry.”

“Resonance,” Vennock said. “In science, engineering, music. If you sing the right note at a glass, it can vibrate and shatter. If you bombard a warp field with the right tune, it can modulate or collapse. And not because you forced these things, but because you pushed them toward a path of least resistance. If someone is making music of hulls and panels, maybe the principle is the same.”

Donis looked up at her, traceries of fatigue sharpening into something like interest. “I’d prefer a practical explanation, a hard explanation, than all the talk of faith and the supernatural.”

Ayres permitted himself the suggestion of a sympathetic smile. “One thing we like to look for in Starfleet is the rational explanation.”

Parr sipped tea that had gone lukewarm minutes ago. “Would you tell us about your lanes,” she said. “Not the ones people write down. The ones you actually run. The market stops, the quiet places to rest and resupply?”

Donis’s shoulders lowered a fraction. “The reasons we don’t tell people should be pretty clear.”

“I hope that fighting alongside you is some level of reassurance,” Ayres said.

That got the closest thing to a laugh so far from the older man. “Promise to do more of that and people will be lining up to share some maps.”

“Our mission is one of rendering aid to people like you. We’d rather not fight, but we won’t back down if we must,” Ayres said. “Would you walk us through your last three runs?”

They did. The conference table became a communion table, the screens around the room lighting up with charts and adjustments made on PADDs. Donis drew with her finger, not touching any screen; a freighter captain’s habit of keeping maps where they can’t be stolen. The young man supplied more precision and practicalities. They spoke of a station called Lippard’s Rest; of a refuelling rig that sold illicit goods on the side; of a ‘chapel station’ that catered for the peaceful faithful of many worlds.

“Where do the pilgrims prefer to intervene?” Ayres asked. “At the beginning of runs, when morale is high? At the end, when people are tired?”

“Where the view is worst,” Donis said, deadpan. “Where you can’t see them coming? I said before, you can’t predict it.”

“And do they take anything?” Parr added. “Cargo. Food. Fuel. People to ransom?”

The young man shook his head slowly. “Not like raiders we used to know. They sometimes take parts from ships. I’ve heard of them taking parts from ships and leaving the rest of the ship, and the crew alone. And the stories say they do it all in silence. I don’t know if I believe that.”

“Do the pilgrims have places?” Parr asked. “Homes? Stations that you avoid? A place people go if they want to join.”

“Yes,” the elder said. “Old stations nobody wanted. Hulks. Out in the dark on the old routes, sometimes we see a ring of junk lit with lights.”

Ayres made the face he reserves for facts he intends to put in his pocket and take out later. “And stories? Names? I heard ‘prophet’. I’ve heard ‘veil’ and ‘threshold’. Anything else?”

The young man rubbed at a smear on his sleeve until it proved immovable. “They say, ‘entropy is the cradle of light,’” he said reluctantly, as if repeating it might stain his mouth.

Parr nodded. “We’ve heard that.”

“They call their little boxes reliquaries,” Donis added. “Black. Warm. They bring them in like gifts and set them down with reverence. We once found one in our engineering before I threw it out an airlock.” She looked briefly pleased.

Ayres and Parr both looked at each other, then at Vennock. The black box in their own secured lab sat dormant like an unwanted guest. “We found one of those. We plan to study it,” Ayres said mildly. “Carefully.”

“Stupid,” Donis said. “Follow my example.”

Ayres let the moment hang. Then, quietly: “We’d like to keep you with us awhile. We’ll form a caravan.” He glanced at Parr, who inclined her head. “We’ll keep a watchful patrol around you and coordinate routes together. I won’t lie: we don’t know all we need to yet. But we know enough to be useful. And we’re quick learners.”

Donis studied him. “You don’t have to do this,” she said. Not challenging. A statement of etiquette from a culture where debts are tallied with care.

“We do,” Ayres said. “We signed up to do exactly this.” He paused. “We also want to.”

“That’s worse,” Donis said, with a dry intelligence Parr liked very much. “People who want to help can be exhausting.”

Lin tugged at Donis’s sleeve, eyes on the viewport. “Is that ours?” she asked. The Kelzora floated in escort on the Farragut’s flank, battered and obstinate.

“That’s ours,” Donis said, and the smile that found her mouth looked like a crack in armour that had been waiting for a particular weather.

Ayres took the moment. “Last questions for now,” he said, “or last facts you want on our table before we go back to work?”

The older man lifted one finger gracefully. “Only this,” he said. “Pilgrims don’t mind if you don’t believe at first. They’re patient. They seem to wait until the exact moment that you’re vulnerable to their song. Build your plans with that in mind.”

Ayres looked down the length of the table. “We’ll build our plans together,” Ayres said. “Thank you.”

They rose. Parr took Donis aside for a minute, a brief exchange about manoeuvres, watches, and the shape of authority when you place one ship inside another’s shadow. Vennock crouched to Lin’s height and asked if she wanted to see sickbay. Ayres asked the older man if he would be willing to take dinner with him and talk more about their worlds, their societies, their histories.

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet